| Robert Frost | |

|---|---|

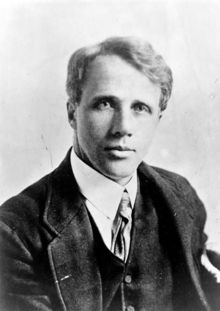

Robert Frost (1941) | |

| Born | Robert Lee Frost March 26, 1874 San Francisco, California, United States |

| Died | January 29, 1963 (aged 88) Boston, Massachusetts, United States |

| Occupation | Poet, Playwright |

| | |

| Signature | |

Robert Lee Frost (March 26, 1874 – January 29, 1963) was an American poet. He is highly regarded for his realistic depictions of rural life and his command of American colloquial speech.[1] His work frequently employed settings from rural life in New England in the early twentieth century, using them to examine complex social and philosophical themes. A popular and often-quoted poet, Frost was honored frequently during his lifetime, receiving four Pulitzer Prizes for Poetry.

Biography

Early years

Robert Frost was born in San Francisco, California, to journalist William Prescott Frost, Jr., and Isabelle Moodie.[1] His mother was of Scottish descent, and his father descended from Nicholas Frost of Tiverton, Devon, England, who had sailed to New Hampshire in 1634 on the Wolfrana.[citation needed]

Frost's father was a teacher and later an editor of the San Francisco Evening Bulletin (which later merged with the San Francisco Examiner), and an unsuccessful candidate for city tax collector. After his death on May 5, 1885, the family moved across the country to Lawrence, Massachusetts, under the patronage of (Robert's grandfather) William Frost, Sr., who was an overseer at a New England mill. Frost graduated from Lawrence High School in 1892.[2] Frost's mother joined the Swedenborgian church and had him baptized in it, but he left it as an adult.

Although known for his later association with rural life, Frost grew up in the city, and published his first poem in his high school's magazine. He attended Dartmouth College for two months, long enough to be accepted into the Theta Delta Chi fraternity. Frost returned home to teach and to work at various jobs – including helping his mother teach her class of unruly boys, delivering newspapers, and working in a factory as a lightbulb filament changer. He did not enjoy these jobs, feeling his true calling was poetry.

Adult years

In 1894 he sold his first poem, "My Butterfly: An Elegy" (published in the November 8, 1894, edition of the New York Independent) for $15. Proud of his accomplishment, he proposed marriage to Elinor Miriam White, but she demurred, wanting to finish college (at St. Lawrence University) before they married. Frost then went on an excursion to the Great Dismal Swamp in Virginia, and asked Elinor again upon his return. Having graduated, she agreed, and they were married at Harvard University[citation needed], where he attended liberal arts studies for two years.

He did well at Harvard, but left to support his growing family.[3][4][5] Shortly before dying, Robert's grandfather purchased a farm for Robert and Elinor in Derry, New Hampshire; and Robert worked the farm for nine years, while writing early in the mornings and producing many of the poems that would later become famous. Ultimately his farming proved unsuccessful and he returned to the field of education as an English teacher at New Hampshire's Pinkerton Academy from 1906 to 1911, then at the New Hampshire Normal School (now Plymouth State University) in Plymouth, New Hampshire.

In 1912 Frost sailed with his family to Great Britain, living first in Glasgow before settling in Beaconsfield outside London. His first book of poetry, A Boy's Will, was published the next year. In England he made some important acquaintances, including Edward Thomas (a member of the group known as the Dymock Poets), T.E. Hulme, and Ezra Pound. Although Pound would become the first American to write a (favorable) review of Frost's work, Frost later resented Pound's attempts to manipulate his American prosody. Surrounded by his peers, Frost wrote some of his best work while in England.

As World War I began, Frost returned to America in 1915 and bought a farm in Franconia, New Hampshire, where he launched a career of writing, teaching, and lecturing. This family homestead served as the Frosts' summer home until 1938, and is maintained today as The Frost Place, a museum and poetry conference site. During the years 1916–20, 1923–24, and 1927–1938, Frost taught English at Amherst College, in Massachusetts, notably encouraging his students to account for the sounds of the human voice in their writing.

For forty-two years – from 1921 to 1963 - Frost spent almost every summer and fall teaching at the Bread Loaf School of English of Middlebury College, at its mountain campus at Ripton, Vermont. He is credited as a major influence upon the development of the school and its writing programs; the Bread Loaf Writers' Conference gained renown during Frost's time there.[citation needed] The college now owns and maintains his former Ripton farmstead as a national historic site near the Bread Loaf campus. In 1921 Frost accepted a fellowship teaching post at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, where he resided until 1927; while there he was awarded a lifetime appointment at the University as a Fellow in Letters.[6] The Robert Frost Ann Arbor home is now situated at The Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan. Frost returned to Amherst in 1927. In 1940 he bought a 5-acre (2.0 ha) plot in South Miami, Florida, naming it Pencil Pines; he spent his winters there for the rest of his life.[7]

Harvard's 1965 alumni directory indicates Frost received an honorary degree there. Although he never graduated from college, Frost received over 40 honorary degrees, including ones from Princeton, Oxford and Cambridge universities; and was the only person to receive two honorary degrees from Dartmouth College. During his lifetime, the Robert Frost Middle School in Fairfax, Virginia, the Robert L. Frost School in Lawrence, Massachusetts, and the main library of Amherst College were named after him.

Frost was 86 when he spoke and performed a reading of his poetry at the inauguration of President John F. Kennedy on January 20, 1961. He died in Boston two years later, on January 29, 1963, of complications from prostate surgery. He was buried at the Old Bennington Cemetery in Bennington, Vermont. His epitaph quotes a line from one of his poems: "I had a lover's quarrel with the world."

Frost's poems are critiqued in the Anthology of Modern American Poetry (Oxford University Press) where it is mentioned that behind a sometimes charmingly familiar and rural façade, Frost's poetry frequently presents pessimistic and menacing undertones which often are either unrecognized or unanalyzed.[8]

One of the original collections of Frost materials, to which he himself contributed, is found in the Special Collections department of the Jones Library in Amherst, Massachusetts. The collection consists of approximately twelve thousand items, including original manuscript poems and letters, correspondence, and photographs, as well as audio and visual recordings.[9] The Archives and Special Collections at Amherst College also holds a collection of his papers.

Personal life

Robert Frost's personal life was plagued with grief and loss. In 1885 when Frost was 11, his father died of tuberculosis, leaving the family with just eight dollars. Frost's mother died of cancer in 1900. In 1920, Frost had to commit his younger sister Jeanie to a mental hospital, where she died nine years later. Mental illness apparently ran in Frost's family, as both he and his mother suffered from depression, and his daughter Irma was committed to a mental hospital in 1947. Frost's wife, Elinor, also experienced bouts of depression.[6]

Elinor and Robert Frost had six children: son Elliot (1896–1904, died of cholera); daughter Lesley Frost Ballantine (1899–1983); son Carol (1902–1940, committed suicide); daughter Irma (1903–1967); daughter Marjorie (1905–1934, died as a result of puerperal fever after childbirth); and daughter Elinor Bettina (died just three days after her birth in 1907). Only Lesley and Irma outlived their father. Frost's wife, who had heart problems throughout her life, developed breast cancer in 1937, and died of heart failure in 1938.[6]

Selected works

Poems

|

|

|

Poetry collections

- North of Boston (David Nutt, 1914; Holt, 1914)

- Mending Wall

- Mountain Interval (Holt, 1916)

- The Road Not Taken

- Selected Poems (Holt, 1923)

- Includes poems from first three volumes and the poem The Runaway

- New Hampshire (Holt, 1923; Grant Richards, 1924)

- Several Short Poems (Holt, 1924)[1]

- Selected Poems (Holt, 1928)

- West-Running Brook (Holt, 1928? 1929)

- The Lovely Shall Be Choosers (Random House, 1929)

- Collected Poems of Robert Frost (Holt, 1930; Longmans, Green, 1930)

- The Lone Striker (Knopf, 1933)

- Selected Poems: Third Edition (Holt, 1934)

- Three Poems (Baker Library, Dartmouth College, 1935)

- The Gold Hesperidee (Bibliophile Press, 1935)

- From Snow to Snow (Holt, 1936)

- A Further Range (Holt, 1936; Cape, 1937)

- Collected Poems of Robert Frost (Holt, 1939; Longmans, Green, 1939)

- A Witness Tree (Holt, 1942; Cape, 1943)

- Come In, and Other Poems (1943)

- Steeple Bush (Holt, 1947)

- Complete Poems of Robert Frost, 1949 (Holt, 1949; Cape, 1951)

- Hard Not To Be King (House of Books, 1951)

- Aforesaid (Holt, 1954)

- A Remembrance Collection of New Poems (Holt, 1959)

- You Come Too (Holt, 1959; Bodley Head, 1964)

- In the Clearing (Holt Rinehart & Winston, 1962)

- The Poetry of Robert Frost (New York, 1969)

- A Further Range (published as Further Range in 1926, as New Poems by Holt, 1936; Cape, 1937)

- Nothing Gold Can Stay

- What Fifty Said

- Fire And Ice

- A Drumlin Woodchuck

Plays

- A Way Out: A One Act Play (Harbor Press, 1929).

- The Cow's in the Corn: A One Act Irish Play in Rhyme (Slide Mountain Press, 1929).

- A Masque of Reason (Holt, 1945).

- A Masque of Mercy (Holt, 1947).

Prose

- The Letters of Robert Frost to Louis Untermeyer (Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1963; Cape, 1964).

- Robert Frost and John Bartlett: The Record of a Friendship, by Margaret Bartlett Anderson (Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1963).

- Selected Letters of Robert Frost (Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1964).

- Interviews with Robert Frost (Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1966; Cape, 1967).

- Family Letters of Robert and Elinor Frost (State University of New York Press, 1972).

- Robert Frost and Sidney Cox: Forty Years of Friendship (University Press of New England, 1981).

- The Notebooks of Robert Frost, edited by Robert Faggen (Harvard University Press, January 2007). [2]

Published as

- Collected Poems, Prose and Plays (Richard Poirier, ed.) (Library of America, 1995) ISBN 978-1-88301106-2.

Pulitzer Prizes

- 1924 for New Hampshire: A Poem With Notes and Grace Notes

- 1931 for Collected Poems

- 1937 for A Further Range

- 1943 for A Witness Tree

Notes

- ^ a b "Robert Frost". Encyclopædia Britannica (Online edition ed.). 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-21.

- ^ Ehrlich, Eugene; Carruth, Gorton (1982). The Oxford Illustrated Literary Guide to the United States. vol. 50. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195031865.

- ^ Nancy Lewis Tuten; John Zubizarreta (2001). The Robert Frost encyclopedia. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 145. ISBN 9780313294648. Retrieved 17 July 2010. "Halfway through the spring semester of his second year, Dean Briggs released him from Harvard without prejudice, lamenting the loss of so good a student."

- ^ Jay Parini (2000). Robert Frost: A Life. Macmillan. pp. 64–65. ISBN 9780805063417. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ^ Jeffrey Meyers (10 April 1996). Robert Frost: a biography. Houghton Mifflin. Retrieved 17 July 2010. "Frost remained at Harvard until March of his sophomore year, when he decamped in the middle of a term...."

- ^ a b c Frost, Robert; Poirier, Richard (ed.); Richardson, Mark (ed.) (1995). Collected Poems, Prose, & Plays. The Library of America. vol. 81. New York: Library of America. ISBN 188301106X.

- ^ Muir, Helen (1995). Frost in Florida. Valiant Press. pp. 41. ISBN 0963346164.

- ^ Nelson, Cary (2000). Anthology of Modern American Poetry. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 84. ISBN 0195122704.

- ^ "Robert Frost Collection". Jones Library, Inc. website, Amherst, Massachusetts. Retrieved 2009-03-28.

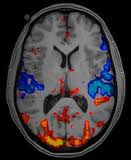

Brain scans pinpoint how chocoholics are hooked. This headline appeared in The Guardian a couple years ago above a science story that began: "Chocoholics really do have chocolate on the brain." The story went on to describe a study that used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to scan the brains of chocoholics and non-cravers. The study found increased activity in the pleasure centers of the chocoholics' brains, and the Guardian report concluded: "There may be some truth in calling the love of chocolate an addiction in some people."

Brain scans pinpoint how chocoholics are hooked. This headline appeared in The Guardian a couple years ago above a science story that began: "Chocoholics really do have chocolate on the brain." The story went on to describe a study that used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to scan the brains of chocoholics and non-cravers. The study found increased activity in the pleasure centers of the chocoholics' brains, and the Guardian report concluded: "There may be some truth in calling the love of chocolate an addiction in some people." The chocoholic study may seem trivial, but is just one of many that Beck analyzes. Another is a 2006 New York Times study of glossolalia—speaking in tongues—which documented decreased activity in the prefrontal cortex during this religious practice. In the article, the lead scientist describes this result as consistent with the claims of the speakers that they lack control over their utterances, leaving the impression that the brain image supports the belief that people who speak in tongues are speaking the words of God. But nothing could be further from the truth. The most that we can conclude, Beck argues, is this: When practitioners claim they are in a different mental state when speaking in tongues than they are when gospel singing (the comparison condition), their brains corroborate that claim. But that's not an amazing claim. Indeed, it's again a claim that most of us would readily accept, just on the practitioners' say-so. As one media critic asked at the time: "If your test subject tells you he likes ice cream, what do we learn from the fact that his brain thinks so too?"

The chocoholic study may seem trivial, but is just one of many that Beck analyzes. Another is a 2006 New York Times study of glossolalia—speaking in tongues—which documented decreased activity in the prefrontal cortex during this religious practice. In the article, the lead scientist describes this result as consistent with the claims of the speakers that they lack control over their utterances, leaving the impression that the brain image supports the belief that people who speak in tongues are speaking the words of God. But nothing could be further from the truth. The most that we can conclude, Beck argues, is this: When practitioners claim they are in a different mental state when speaking in tongues than they are when gospel singing (the comparison condition), their brains corroborate that claim. But that's not an amazing claim. Indeed, it's again a claim that most of us would readily accept, just on the practitioners' say-so. As one media critic asked at the time: "If your test subject tells you he likes ice cream, what do we learn from the fact that his brain thinks so too?"